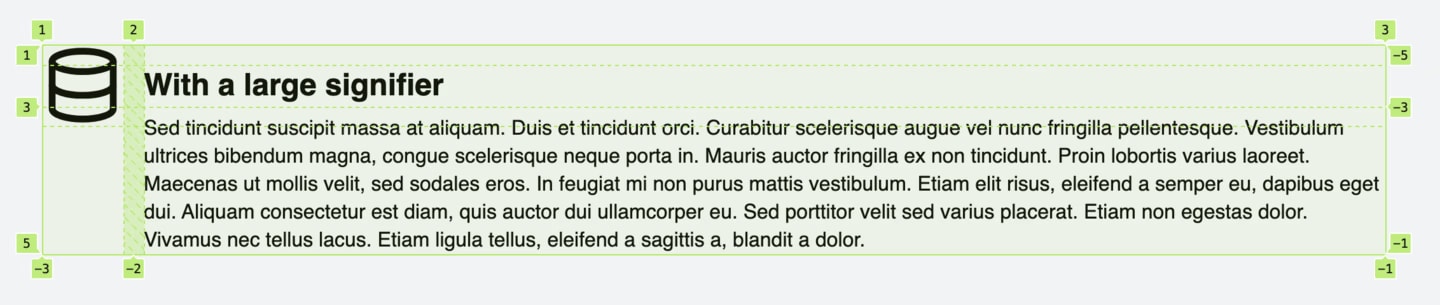

A clever use of CSS grid from Jay Freestone to accomplish a particular variation of the media object design pattern (where the image is centered with the title) without any magic numbers anything that isn’t flexible and resiliant.

The trick is to use an “extra” row above and below the title:

The image goes on the first three rows in the first column, and the content goes in the last three rows in the second column using named grid areas:

grid-template-areas:

'signifier .'

'signifier content'

'signifier content'

'. content';Read Jay’s post for a little more trickery required to make it entirely resilient.

I love the kind of post that zeroes in on the mental model behind CSS grid like this. It’s like… how can I slice up this design with arbitrary columns and rows, knowing that I can place things on arbitrary rectangular combinations of cells with any type of alignment, to best suit this design?

Direct Link to Article — Permalink

The post Bulletproof flag components appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.

source https://www.jayfreestone.com/writing/bulletproof-flag/